Introduction to swim touring

I started swimming front crawl in 2021. By swimming, I mean suffocating every 15 metres. I could not handle the 25m pool opposite my house.

I have loved water ever since I learnt to swim, but I was only ever taught breaststroke. I had the vague idea of doing a triathlon, so I thought I would just get on with it and teach myself front crawl. How hard could it be? Hard.

When you practise swimming on your own, you have no way of looking at your own body position, you come across a thousand different bits of advice online:fingers close together, no, slightly apart; butterfly pattern with your hand, no butterfly pattern; straight arms, 90° angle…

“This is it”, I decided. “Three weeks of exactly zero progress. One more week. If I do not see any improvement, I quit.” Three sessions later, I was still far slower than the man who often swam at the same time as me and who was missing a limb, but I could complete one, sometimes one and a half or two lengths without a break. It was not revolutionary, but it was progress.

Fast-forward three years and I have crossed Lake Como unassisted, swum along various shores as an alternative to a short walk, and I am more comfortable than ever in open water.

Last september, after deciding to take a break from ultra-cycling, I decided to take up swim-touring. I would swim along the coast of Normandy from the Mont Saint-Michel to Granville over five days, a few kilometres at a time. Not a race, not a challenge, not something crazy, just a fun experiment. I needed to do something fun, something for myself, to get away from the pressure I had been putting on myself to always go farther, longer, whatever my state of exhaustion.

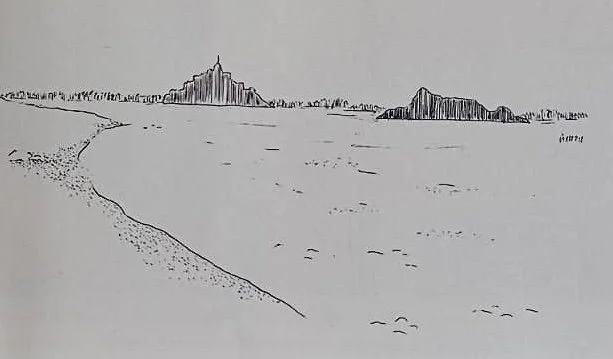

The Mont Saint-Michel, © Hortense Gesquière

DAY 1: 5.2km, 1h36min

Monday, 7:32am train from Paris to Granville, Normandy. My friend Hortense is accompanying me. She will be walking the coastal path while I swim along the coast bit by bit every day, towing my own kit. From Granville, we catch the first bus to Genêts, the start of my journey.

I am armed with a tow float, a flotation device tied to my waist that makes me more visible, and allows me to hold on to something if I need a break from swimming. Additionally, mine has a large pocket inside it, which I will be using as my one and only piece of luggage to store my phone, a change of clothes and toiletries.

I look towards the sea at the end of the sandy path. I am short-sighted and my glasses are packed away already, but I am pretty sure I can recognise the landscape of an unswimmable low tide.

The Mont Saint-Michel bay, the bay linking Brittany and Normandy, has the largest tidal range in Europe: the water line can withdraw up to 15km. I have spent most of my holidays on the Norman coasts since I was a toddler. I grew up with the tidal calendar etched in my brain. My mother would sometimes pressure us to eat up our lunch quickly or we’d ‘miss the sea’. More often than not, we had a two- hour window once a day where we could go for a swim. After high tide, you have to wait another 24 hours before your next chance. Walking to the water at low or ebbing tide is a bad idea: if you do not get bored, tired or sunburnt before reaching the edge, you will find that you need to walk 100m more to have water above your ankles. Another 100m for water around the knees.

The same tide will look very different from one beach to the next due to the coastline and the incline of each beach. If you do not know the particular beach, you do not know what it may look like. Three kilometres away from my mother’s house lies a beach where locals recommend people do not bring their children along as low sand banks are particularly treacherous at rising tide. Two kilometres farther, there is a perfectly safe spot to bathe. They look the same to the unsuspecting tourist.

This crash course on tides was to highlight how familiar I thought I was with the area I was going to swim along, just 40km south of where I grew up. However, I managed to underestimate the tide at my starting point. Due to train times, I knew we would arrive at ebbing tide, but I thought I would still have a shot at swimming if I hurried up.

The situation is comical as there is no water in view. I am standing on the beach, all geared up for a long sea swim. Groups of school kids are setting off to cross the bay on foot to go over to the Mont Saint-Michel. I hope they do not see me.

Now, I have to make the best of it. I wave goodbye to my friend; neither of us really know what I will do next. I am now ankle-deep in tangue, the dark sticky clay-like sand so typical of some beaches around here. I turn on my GPS to find the route I had planned, more or less a straight line to avoid hugging the coastline to the next village. I will just have to walk along it instead of swimming.

I walk a bit farther to find out whether there is any chance I can swim. The answer is clearly no, but I spot a narrow channel of water between sand banks, meandering in the right direction. At its deepest points, the little river goes up to my knees. In my books, this qualifies as some sort of sea activity. I waddle in the water and check my watch: 1:50min/100m. My ocean swim pace is usually over 2:00min/100m, slower, but not by much; it is not that easy to walk through water with an uneven and clay-like surface at the bottom.

I am starting to get quite warm. My black wetsuit is getting wet from the inside. I crave an impossible dip. I look down at the shallow water carrying lots of tangue particles and wonder what it would be like to try to breathe through such a soup.

Heck, I am here to have fun in the water, and I will do that one way or another. I clip the strap of my bag around my waist and lie down. After a bit of experimenting, I unlock a new technique: lying down, facing the water but with my head fully out, I dig my fingers vertically into the bottom and haul up my body. It feels like assisted climbing, but in a horizontal position. I wonder whether I will get muscle pain from this the next day (I did).

The channel changes direction and starts heading out towards the ocean. I am already quite far out, so I get up and walk again, following the coastline.

I splash a lot of thin, wet tangue around as I walk and I look like I have just got out of a mud bath.

I spot Hortense’s long silhouette on the beach and I eventually merge paths with her just before reaching St Jean Le Thomas. We laugh about today’s exploits and admire the scenery under the bright sunshine. We find our hut on the beach, our home for the night. I rinse off my legs, shower, and we meet on the deck chairs overlooking the bay to eat biscuits and have tea a.

It’s 5pm but the sun is shining so bright on this warm September day that I apply sunscreen. One hour later, we are curled up in bed, looking at the curtain of rain crashing against the windows. Welcome to Normandy.

Day 2: 4km in 1h09min

We sit in the village cafe and eat an almond pain au chocolat from the bakery. The weather is dreary but the drizzle is so light that I can’t say it’s raining. I feel like I am on one of my bike tours; the only times I sit in a bar-tabac for breakfast, among morning smokers and drinkers. It is nice to notice that I am getting the same feelings of adventure and travel with this super-slow travel mode.

We kill time until 12pm, where the tidal current starts to be in my favour. I put on my cap, earplugs, gloves, and I can’t really be bothered to go in. It will probably be fun once I’m in, I tell myself.

Time to wave goodbye to Hortense for what I expect to be a 1.5h to 2h swim session. The sea looks calm but not flat. I will have to swim beyond the wave line and navigate the flow: lowering my front arm and waiting longer than expected before it hits the surface of the water; feeling the pull of the water towards the ocean, signalling a roll coming my way, telling me to take one stroke fewer or one stroke more before my next breath to avoid a salty slap in the face.

Before going in, I had a good look at the landmarks on the way: the car park along the dyke, the village, then the coastal road descending from the top of the cliff to the bottom of the peninsula, my goal for the day, and the last possible landing spot before the coast turns into uninterrupted rocky cliffs. My kit choices are catching up with me: I packed my thick but slightly too big neoprene swim socks. They fill up with water, balloon up, and threaten to part ways with my feet. Every 200m, I curl up in a ball to clumsily pull them up with gloved up fingers. These are the gloves I bought last minute, the only ones I could find, also a bit big. I find that one breath is just enough time to comfortably sort out all my extremities, so the curled up routine sets into my swimming rhythm. Tomorrow, I will tie elastic bands around my ankles and wear my gloves underneath the sleeves of my wet suit.

Wearing earplugs has totally sorted the pressure issues I was experiencing in my sinuses after swimming, and I'm grateful for that. Unfortunately, I knock out my right ear plug when a wave throws my tow float against my hand near my ear.

How far have I gone? My watch says 500m but I've barely started swimming. GPS signal isn't so good in open water; in fact, the swim route I carefully created is pretty useless as it keeps disappearing from my screen. I'm perfecting my technique of looking at my watch face mid stroke, when my hand is in the air and I am breathing. In clear water, I would give it a quick glance underwater, but the thick grey soup I am flowing through does not even allow me to see my hand in front of my face. Another look at my watch: 1.5 km; 1:35m/100m. Is that so? Looking back, the distance seems right, but I've never swum anywhere near that speed, wetsuit or not, and I'm dragging my pack.

Time to curl up again to pull up my socks. My tow float overtakes me. I have my answer. I planned my swim time to benefit from the ebb flow, but I had no idea it would be this strong.

Where is this stupid pier? I'm not feeling tired but I don't want to swim more than planned. I'll have to get closer to the rocks to get a good look. Finally, I see a road that must descend onto the pier. Still, at water level, it’s all just bloody rocks. A curve in the road makes me think that I can guess where the rocks open up for the boats to slide into the water. I am now directly aiming for the coast at a 90° angle aiming for the rocks to the right of the pier so that I don't overshoot due to the current and end up having to fight against the current to land.

My aim is pretty good and I set foot on the concrete just as Hortense is trotting down the road. The strong current combined with a windy coastal path meant that we took the same time to get here swimming and on foot.

My mouth, especially underneath my tongue, feels rough, probably due to the salt water. I'm glad I had covered my entire face in Vaseline before going in. The salt hasn't assaulted my fragile skin as it usually does.

Day 3:4.4 km 1h19min

Spot the swimmer

Putting on a wetsuit in the rain, let alone a wet one, is a real test of patience. Hortense was curled up in a ball over her bag to avoid getting her trousers soaked before it was inevitable. I put my kit on, tie an elastic band around each ankle to avoid my socks slipping off (which worked surprisingly well), cover my face and lips in Vaseline, tuck my gloves under my wetsuit, and I'm almost ready. I head off directly facing the ocean to get away from the rocks.

Today is the big scary day: passing 4 km of rocky cliffs. The descending tide should allow me to have access to at least one bit of sand at the bottom of the rocks, and just before leaving, I spotted on the map a small beach before Jullouville where the river Lude goes into the sea.

Temperature-wise, it feels very cosy. 18° in the water plus my neoprene is a perfect combination. I feel warmer than I did on the walk to the pier. I approach the end of the peninsula. It becomes clear that around the corner is another corner and I'm nowhere near the other side. It makes sense given that I haven't swum 1.5 km yet, but still it feels surprising. Even though I studied the map with great attention, recognising every curve of the shore from the water is once again tougher than I thought.

Many people ask if I'm ever scared when open water swimming. The answer is yes, almost always. On every swim, I blink to the vision of a great white shark inside my eyelids; I ingest a tiny gulp of water and wonder if it might lead to my drowning; I imagine waves throwing my body onto the rocks and cracking my skull. Then, I think. No sharks here. One gulp doesn't make you drown.

When I finally see the cliffs giving way to a flat sandy beach, I immediately fear I will miss the rugged cliff side I had been fearing for two days. It's a dramatic landscape that I am not used to. Seeing the giant chunk of shore exiting the water, from the water, is something I have rarely seen as I have not been on small boats many times. It feels scary, grandiose, and beautiful. The dreary weather adds to the dramatic effect. It is raining but that makes no difference to me and my fellow sea creatures.

I see sharp rocks protruding out of the water just before the big beach. I had spotted them on the maritime map, but thought they would be much farther out at sea. There is a break in the line. Should I swim into the gap, hoping it's an actual gap rather than a few metres of lower rocks that just skim the surface? I see a big sharp bit sticking out, maybe a few metres in front of the gap, maybe in the middle of it; I can't tell. I'm not taking any chances. I'll go wide and avoid the whole lot.

I get out in the rain, say bye to my dreaded and beloved rocky cliff, and start changing. I've once again arrived before her thanks to the tidal current.

Day 4: 4.3km in 1h29min

The wind is extremely strong and goes the way I want it to, more or less. On top of that, I will once again manage to get in the water at the perfect time to get carried by the current.

Or so I thought. The waves come crashing one after the other, and I struggle to even get past the bulk of them and into a swimmable zone. I'm heavily out of breath when I start swimming and get wiped out, tossed and turned a couple of times by some large waves that take me by surprise. I head back towards the beach and walk along the water for a bit.

As far as I can see, waves keep curling up, foaming up, and crashing. Going further at sea won't help. I go back in and accept my fate. No arriving before Hortense today, no leisurely swim, no gentleness. I will do my 4km in a mix of sea walking and swimming, which yield a surprisingly similar speed in these conditions.

The waves are so close to each other that all I can see ahead of me is a bunch of frothy bubbles. In fact, it looks a bit like a sea of whipped cream. I indulge in that thought. If I imagine I'm making my way through whipped cream instead of an unkind sea, the journey will feel much sweeter. When the hail comes, I go back to swimming. The little amount of skin I have on display gets too painful if I let it get hit by the hail while sea walking. I finally exit the water after 1h30min. I walk along the beach for a bit. I can barely see the coast a few hundred metres away. I'm enjoying this privileged moment alone, in conditions I would find horrendous were I wearing normal clothes, but in my wetsuit, I can enjoy the surrounding wetness and the curtain of rain in peace. I wait for the rain to calm down and I put on my shoes and jacket over my wetsuit before heading to the B&B where Hortense is waiting for me.

Day 5: 3km in 1h10min

Through my shortsightedness, I can use two big towers as a landmark to aim for. Beneath them lies my target beach, the last beach before the harbour. Swimming is alright today but very tiring: I aim diagonally out at sea to compensate for the current pushing me towards the town I left this morning and have to navigate irregular waves, with the occasional one big enough to topple me.

I have no problem swimming among waves. You get used to the rolling feeling, when to look up, when not to… With a tow float, it is a different story. Your body may clear a wave, but then the bag rides along its crest and pulls you towards it. Try diving underneath a wave to dodge it, your spine will get yanked up by the tow float. Repeat a gentle tug of the spine 100 times, and it becomes quite unpleasant.

I always knew that due to tide and train times, I may have to end my journey a couple of beaches before the harbour. But there are a couple of cliffs I have to go around to reach the town, and I like that now. Swimming along a flat beach is reassuring but lacks charm.

My tediously slow progress is barely noticeable. I eventually ask myself: "Am I having fun?". I feel a wave of the "soldier on" feeling. This is a feeling I have during my cycling ultra events, when I spend at least 12 hours a day in the saddle.

I am definitely not enjoying myself and I resort to switching off my brain. The idea is that if I can't think of whether I am miserable, then I can't possibly feel miserable. I did not book one week of holiday with my best friend as a way of healing my ultra wounds to feel ultra feelings. I turn sideways and exit the water without looking back. I will not even Granville, and no one, including me, cares.

Hortense meets me on the beach, I change in the chilly wind, and we proceed to walk along the coastal path while we chat and eat brioche and milk chocolate we bought in the morning.

I feel like we are eight years old again, having a snack after our frankly lazy swimming lesson where we, as usual, did very little swimming and a lot of chatting while hanging off the edge of the pool.

This is what I came here for, this is what I wanted. This is how I want to feel today.

Open Water Swimming Tips

Plan with tides and currents in mind.

Practise safety first: Use a tow float and a high-vis cap for visibility. Always have an exit plan in case conditions worsen, such as identifying accessible beaches or sandbanks.

Choose the right gear for you: I need ear plugs, you may need a nose clip, earphones…

Familiarise yourself with landmarks: before swimming, identify clear visual markers along the coast to help you navigate, maintain a straight line and estimate distances. This is especially useful as GPS signal is unreliable.

Adapt to changing conditions: be prepared to adjust your route or swimming technique based on unexpected challenges like rough waves, strong currents, or submerged hazards.

Stay within your comfort zone: open water swimming can be intimidating, but focusing on your breathing and surroundings helps reduce fear. Embrace the beauty and unpredictability of the sea.